In March of 2004 Jamie Pilarczyk embarked on what is undoubtedly her greatest adventure to date. Wanting to make a difference in this world, she joined the Peace Corps and began a 27- month journey.

Jamie began her trip by traveling from her home in Tampa, Fla., to Philadelphia where she met the other volunteers that would be working in Morocco. There they were split into two focal groups, one in health, the other the environment. Three days later, Jamie and the 39 other volunteers flew to Morocco where they spent the next three months training in the country. Their instruction consisted of language acquisition, cultural information and technical aspects that were needed to survive. About the end of May, Jamie was placed with her host family. When asked about her first impression, Jamie said, cI remember vividly seeing the shanty towns, donkeys and dirty roadsides we passed as I looked through the window on our bus from the airport in Casablanca to the capital city of Rabat. I kept praying that God wouldn’t have my host family living in the shacks I was staring at. Of course, I lived in conditions far better and I was well taken care of, but I was probably in culture shock for the first six months.”

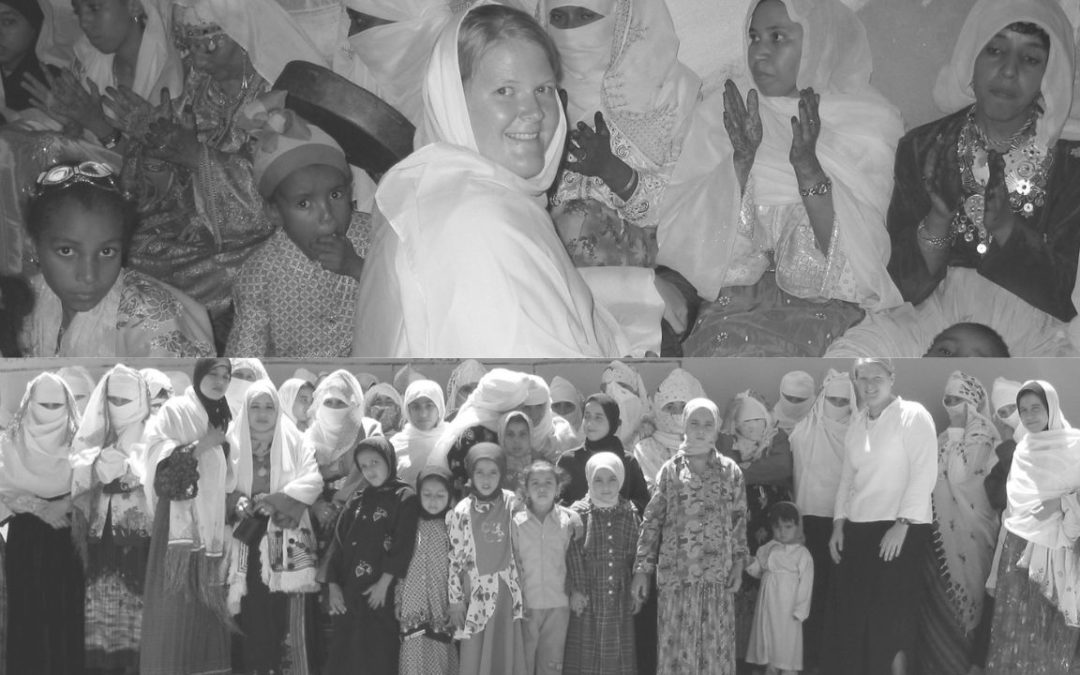

Although Jamie was placed with a host family, they were not Americans, and were not westernized. The closest Peace Corps volunteer to her was “two cab rides and an hour and a half away.” Jamie saw this volunteer once a week when they traveled to the province capital to shop and check email. In the cities of Morocco, the people were more westernized. But Jamie lived in “south-west Morocco, on the border of the Sahara desert. The village is called Ait Ahmed (city) in the province of Tiznit (like a county).” Village life was far different than that of the city. “We didn’t have electricity until the second year that I was there. I had running water in the house I rented but my host family only had a cistern (holding tank stored in the basement of their house). We had one paved road that led from our village out to the province capital, which was a blessing.” The differences between the cities and the villages were also seen culturally. There, as in most Muslim countries, women wear head coverings. According to Jamie, “Women are not addressed by men unless they are related, men and women eat separately, girls were not allowed in school until 1990 and women have different roles for labor.” In essence, Jamie was forced to be creative in her approach to working with the population-at large. Jamie’s main role was in health education, primarily in the areas of hygiene and sanitation. “I did a lot of health education — how to brush teeth, wash hands, etc. I also wrote grants for dentures, a bridge, a three-stall bathroom at the local mosque, a small portable incinerator, as well as a Glucometer for the health clinic. My favorites by far were the educational fairs for the younger girls to learn about women’s health as well skills such as rug making.”

Another major aspect of Jamie’s work there involved HIV/AIDS education. This proved to be one of her bigger challenges. “As a woman volunteer, I had to be careful how I talked about HIV/AIDS, since it is still a sort of taboo subject. It is assumed that everyone (well, at least the girls) is a virgin at marriage and that they will remain faithful during the marriage. The truth, though, is that many men are sexually active far before marriage and are often not faithful afterwards. I know AIDS could become a serious problem there without education. So, at one of our twice-yearly festivals (men-only since women do not go to market which is where the festival is held), I had a table set up and passed out HIV/AIDS brochures in Arabic with pictures of how I could talk about AIDS with the men. In the beginning, I went to a few individuals to explain the brochure, but their obvious uncomfortable reaction made me realize that education would be more effective with these men if it were to come from the male doctor. My future attempts at HIV/AIDS education were to host educational programs and then have the doctor or female nurse address the crowd (women only, or men only).” While most of her time was spent with her people group, Jamie did have a chance to travel and see some of the sites. “I traveled from the Sahara Desert to the Straights of Gibraltar. On my own I also traveled to Spain and to Paris. And on my way home from service, I also saw Egypt.” When asked if she would recommend the experience to others, Jamie stated “Definitely. Keep in mind though that only a small percentage of volunteers make it the full two years. It is a big commitment that is definitely not all roses, but it is abundantly rewarding personally if you make it through it.” She is a graduate of Auburn University and an alumna of Omicron Chapter.